February is Black History Month, and we would like to take this opportunity to share stories of influential, black members of the early church in America.

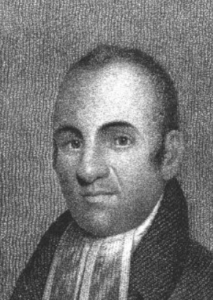

Lemuel Haynes was born on July 18, 1753 in Connecticut. He was abandoned by his parents when he was just five months old. Haynes was raised in indentured servitude by the Rose family in Massachusetts. The Roses treated Lemuel as one of their own children, including instruction in Christianity and family worship. When his indenture ended, Haynes joined as a Minuteman and, in October 1776, joined the Continental Army. Lemuel served until November 1776, when he contracted typhus and was relieved of duty. After the American Revolution, Haynes demonstrated his interests and talents for theology and ministry. “Haynes was a determined, self-taught student who pored over Scripture until he could repeat from memory most of the texts dealing with the doctrines of grace.” Haynes began his formal training by studying Greek and Latin with two clergymen and was licensed to preach in 1780. Five years later, he became the first African-American ordained by any religious body in America. In 1804, Middlebury College awarded Haynes an honorary Master’s degree, the first for an African American. He began his life of ministerial work as a founding member and pastor to the church in Middle Granville, Massachusetts. He served in Middle Granville for five years, and then he was ordained by the Association of Ministers in Connecticut. Haynes completed his ordination in 1785 while serving a church in Torrington, Connecticut. However, he was never offered the pastorate of that church due to racial prejudice and resentment among churches in the area. In 1783, Haynes married twenty-year-old Elizabeth Babbit, a white schoolteacher and member of his congregation. The couple went on to have ten children between 1785 and 1805. In 1788 Haynes left the Torrington congregation and accepted a call to pastor in Vermont, where he served an all-white congregation for thirty years—a relationship between pastor and congregation rare in Haynes’s time and today. During his time teaching in Vermont, the church grew from forty-two congregants to three hundred and fifty.

Amanda Berry Smith was an evangelist, missionary, and founder of an orphanage for African American children. Amanda was born into slavery in 1837 in Long Green, Maryland, to parents Samuel and Miriam, who were held on adjacent farms. Eventually, her father was able to work for wages at night to purchase freedom for himself and his family. Amanda attempted to pursue formal education but could not because a school was not available or it was extremely difficult for an African American child to get a proper education in a white school. At thirteen, Amanda left home to work as a live-in domestic and began attending a Methodist church. In 1854, she married Calvin Devine and gave birth to a daughter, Mazie. Calvin enlisted in the Union Army but never returned home. In 1855, Amanda was severely ill and dreamed that she was preaching at a camp meeting. When she recovered, she was converted. In 1865, Amanda Berry married James Smith with the dream of becoming a minister’s wife to be able to pursue her dream. Unfortunately, James never became a minister. After his passing, Amanda began to preach and sing at holiness camp meetings and became very popular for both of these talents. In 1878, Amanda Berry Smith traveled to preach in Great Britain, India, and Liberia for eight years. Her time in Africa was particularly difficult, specifically due to illness. When she returned to the U.S. in 1899, she pursued her long-time dream of educating African American children by founding the Amanda Smith Orphanage and Industrial Home for Abandoned and Destitute Colored Children in Illinois.

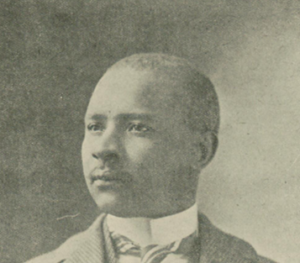

In Topeka, Kansas, an African American newspaper editor, Nick Chiles, announced his candidacy for the United States Senate. Although a black person had not occupied a Senate seat in over 40 years—and would again for 40 more years— Chiles had grown frustrated with Kansas’ current senator’s unwillingness to fight for the voting rights of black people. Chiles’ campaign platform included eight factors, most of them focused on ending segregationist control of the government, re-enfranchising African Americans, and guaranteeing all workers a living wage. It also included a factor that showed the foundation for his claims: “The Holy Bible for my Guide.” However, the Chiles had set up shop in Topeka, Kansas, and he was best known for engaging in one of the greatest evils a late 19th-century Protestant could imagine: the liquor trade. By the 1890s, white newspapers in Topeka were ablaze with complaints of the “notorious negro joints” who was “never punished for the crime.” Chiles later established a more positive reputation through various measures, including voicing his religious perspectives. He joined Topeka’s St. John AME congregation in 1910. While Chiles was a complex figure who “could pose on four sides of everyone question, and come out unscathed,” there was at least one consistent theme and common ground with opposition in Chiles’s lifelong anti-racism activism: belief in Christ and the pursuit of Christian principles.